Most Americans don’t know that the U.S.A. has a long history of invading Mexico and stealing land from Mexico. You got the sugar coated politically correct, but wrong version of some of these events in the government run American public schools.

- Prickly Pear Cactus and Eagle Logo

- Mexican Independence from Spain - 1810-1821

- The Santa Anna years – 1833 to 1855

- Texas Revolution - Texas War of Independence - 1835 - 1836

- Americans overthrow Mexican government in California 1846

- Mexican-American War - 1846-48

- 1855 The Church and Military lose power

- Cinco De Mayo - Battle of Puebla - May 5, 1862

- Mexican Revolution - 1910 to 1919/1929

- General Álvaro Obregón - 1920 to 1924

- PRI dictatorship loses power to PAN

- President Felipe Calderon a Mexican version of Richard M. Nixon

Prickly Pear Cactus and Eagle Logo

The Aztecs, then a nomadic tribe,

were wandering throughout Mexico

in search of a divine sign

that would indicate the precise spot upon

which they were to build their capital.

Their god Huitzilopochtli had commanded them

to find an eagle devouring a snake,

perched atop a cactus that grew on a

rock submerged in a lake.

After two hundred years of wandering,

they found the promised sign on a

small island in the swampy Lake Texcoco.

It was there they founded their new capital, Tenochtitlan.

The Aztecs, then a nomadic tribe,

were wandering throughout Mexico

in search of a divine sign

that would indicate the precise spot upon

which they were to build their capital.

Their god Huitzilopochtli had commanded them

to find an eagle devouring a snake,

perched atop a cactus that grew on a

rock submerged in a lake.

After two hundred years of wandering,

they found the promised sign on a

small island in the swampy Lake Texcoco.

It was there they founded their new capital, Tenochtitlan.

Mexican Independence from Spain

September 16 1810-1821

The government of the Spanish Empire, shattered by Napoleon's invasion of Spain, was succeeded by "juntas" in both Spain and the Americas in order to replace the authority of the king, Fernando VII, held hostage by Napoleon in Bayonne, France. The forced removal of Ferdinand VII from the Spanish thrown and his replacement by Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon's brother presented opportunity for Mexican intelligentsia to promote independence in the name of the legitimate Spanish king.

The Mexican War of Independence started on September 16, 1810. The head figure and chief instigator of the Mexican Independence movement was Miguel Hidalgo, the Creole parish priest of the small town of Dolores. On August 24, 1821, representatives of the Spanish crown and Iturbide signed the Treaty of Córdoba, which recognized Mexican independence under the terms of the Plan of Iguala.

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (February 21, 1794 – June 21, 1876), was known simply as Santa Anna and was President of Mexico eleven non-consecutive times over a period of 22 years. President, well dictator would be a better word for it.

Santa Anna was involved in the Battle of the Alamo in 1836 and was soon defeated by Sam Houston's soldiers at the Battle of San Jacinto in1836. After that being captured by the U.S. he gave all of Texas to the U.S.A even though he had no authority to do it.

That later gave the USA the excuse to invade Mexico and steal most of the southwestern states from Mexico.

Santa Anna was also responsible for selling the Gadsden Purchase to the United States, and he shoved a lot of that money into his own pocket.

Of course, these Americas would later

become a problem themselves to the Mexican government,

as they would revolt and overthrow the Mexican government in Texas;

become their own Republic of Texas;

and later become a part of the expanding American Empire.

The Texas Revolution or Texas War of Independence was fought from October 2, 1835 to April 21, 1836 between Mexico and the Texas (Tejas) portion of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas.

Animosity between the Mexican government and the American settlers in Texas began with the Siete Leyes of 1835, when Mexican President and General Antonio López de Santa Anna Pérez de Lebrón abolished the Constitution of 1824 and proclaimed a new anti-federalist constitution in its place. The war began in Texas on October 1, 1835, with the Battle of Gonzales.

The war ended at the Battle of San Jacinto (about 20 miles (32 km) east of modern day downtown Houston) where General Sam Houston led the Texas Army to victory in 18 minutes over a portion of the Mexican Army under Santa Anna, who was captured shortly after the battle. The conclusion of the war resulted in the creation of the Republic of Texas.

With Santa Anna a prisoner, his captors forced him to sign the Treaties of Velasco on May 14. The treaty recognized Texas's independence and guaranteed Santa Anna's life.

The Republic was never recognized by the government of Mexico, and during its brief existence.

On the map the area in yellow is the Texas that succeeded from Mexico,

the area in green and yellow is the area Mexico still claimed.

The USA would later invade this disputed area and

use it as an excuse to start the Mexican-American War

When the US declared war against Mexico, on May 13, 1846,

it took almost two months for definite word of war to get to California.

Then on June 15, 1846, some 30 settlers, mostly U.S. citizens,

staged a revolt and seized the small Mexican garrison in Sonoma.

They raised the "Bear Flag" of the California Republic over Sonoma.

It lasted one week until the U.S. Army, led by Frémont, took over on June 23.

Commodore John Drake Sloat,

ordered his naval forces to occupy Yerba Buena (present day San Francisco) on July 7

and raise the U.S. flag.

The U.S. forces easily took over the north of California;

within days they controlled San Francisco, Sonoma, and Sutter's Fort in Sacramento.

When Stockton's forces, sailing south to San Diego, stopped in San Pedro,

he dispatched 50 US Marines, and entered Los Angeles unresisted on August 13, 1846,

known as the Siege of Los Angeles,

the nearly bloodless conquest of California seemed complete.

Meanwhile, General Stephen W. Kearny, with a squadron of 139 dragoons,

after a grueling march across New Mexico, Arizona and the Sonora desert,

on December 6, 1846, and fought in a small battle with Californio Lancers

at the Battle of San Pasqual near San Diego, California.

Later, their re-supplied, combined force, marched north from San Diego,

entering the Los Angeles area on January 8, 1847,

linking up with Frémont's men.

With U.S. forces totaling 660 soldiers and marines,

they fought and defeated an equal Californio force in the decisive

Battle of Rio San Gabriel, and the next day, January 9, 1847,

they fought the Battle of La Mesa.

On January 12, 1847, the last significant body of Californios surrendered to U.S. forces.

That marked the end of the war in California.

On January 13, 1847, the Treaty of Cahuenga was signed.

The Mexican government, however, refused to acknowledge these concessions, arguing that Santa Anna was not a representative of Mexico, that he had no authority to negotiate on behalf of Mexico, and that he signed away Texas under duress. The Mexican government never ratified the Treaties of Velasco, but did not reopen the war.

Mexico claimed the Nueces River — about 150 miles (240 km) north of the Rio Grande — as its border with Texas; the United States claimed the Rio Grande as the boundary, citing the 1836 Treaty of Velasco. Mexico, however, never ratified this treaty. Regardless, the United States used the treaty to advance its cause.

In 1846, after Texas was admitted into the Union, Polk sent militia under General Zachary Taylor to the Rio Grande to protect Texas. Taylor ignored Mexican demands to withdraw to the Nueces.

On April 24, 1846, a 2,000-strong Mexican cavalry detachment attacked a 63-man U.S. patrol that had been sent into the contested territory north of the Rio Grande and south of the Nueces River. The Mexican cavalry succeeded in routing the patrol.

President Polk had received word of the attack and told Congress on May 11, 1846 that Mexico had "invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil." A joint session of Congress approved the declaration of war.

In the United States, most Whigs in the North and South opposed the war; most Democrats supported it. Joshua Giddings led a group of dissenters in Washington D.C. He called the war with Mexico "an aggressive, unholy, and unjust war," and voted against supplying soldiers and weapons for the war.

In the end the American military under General Winfield Scott occupied Mexico City where they forced the Mexican government to sign the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, on February 2, 1848. The treaty ended the war and gave the U.S undisputed control of Texas, established the U.S.-Mexican border of the Rio Grande River, and ceded to the United States the present-day states of California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and Wyoming.

The treaty gave Mexico US $15,000,000 — less than half the amount the U.S. had attempted to offer Mexico for the land before the opening of hostilities.

The acquisition was a source of controversy at time, especially among U.S. politicians that had opposed the war from the start. A leading U.S. newspaper, the Whig intelligencer sardonically concluded that:

Juárez also caused Spain, Great Britain, and France to invade Mexico

when he declared a moratorium on foreign debt payments around 1861.

Benito Juarez lived in same era as Santa Anna.

The holiday commemorates an initial victory of Mexican forces

led by General Ignacio Zaragoza Seguín

over French forces in the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862.

4,000 Mexican soldiers smashed the French and traitor Mexican army of 8,000 at

Puebla, Mexico, 100 miles east of Mexico City on the morning of May 5, 1862.

However, the Mexican victory at Puebla only delayed the French invasion of Mexico City,

and a year later, the French occupied Mexico.

The French occupying forces placed Maximilian I, Emperor of Mexico on the throne of Mexico;

Maximillian and the French were eventually defeated and expelled in 1867

(Maximilian was executed), five years after the Battle of Puebla.

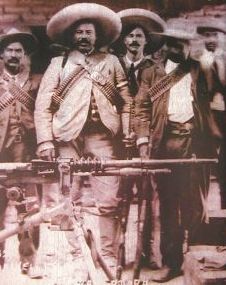

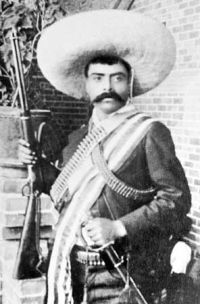

Francisco "Pancho" Villa came from the northern state of Durango and was one of the leaders of the Mexican revolution. Emiliano Zapata Salazar was a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution against the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz that broke out in 1910. He is considered to be one of the outstanding national heroes of Mexico.

Díaz was pressured into holding an election in 1910,

in which Madero was able to gather a significant number of the votes.

Although Díaz was at one time a strong supporter of the one-term limit,

he seemed to have changed his mind and had Madero imprisoned,

feeling that the people of Mexico just weren't ready for democracy.

Once Madero was released from prison,

he continued his battle against Díaz in an attempt to have him overthrown.

During this time, several other Mexican folk heros began to emerge,

including the well known Pancho Villa in the north,

and the peasant Emiliano Zapata in the south,

who were able to harass the Mexican army and wrest control of their respective regions.

Almost 900,000 Mexican immigrants fled to the United States between 1910 and 1920.

The exact end of the "revolutionary period" is open to debate.

From a strictly military standpoint it ended with the

death of the Constitutional Army's primer jefe (First Chief) Venustiano Carranza in 1919,

and the ascension to power of General Alvaro Obregon,

but bloodshed and revolts continued through the Cristero Wars of 1926-1929.

Carranza was followed by others who would fight for political control,

and who would eventually continue with the reforms,

both in education and land distribution.

During this period the PRI political party was established,

which was the dominant political power for 71 years

until Vicente Fox of the conservative PAN party was elected.

He was around in the Pancho Villa days, and he fought Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata. His buddy General Benjamín Hill helped him overthrow the Mexican government and he later became president. Obregón's four years in office were known for the agrarian and anticlerical reforms. He was assassinated in a restaurant on July 17, 1928, by José de León Toral, a Roman Catholic opposed to the Government's policies on religious matters. He was born in Navojoa, Sonora.

The city of Obregon is named after him.

The city of Benjamín Hill is named after his buddy General Benjamín Hill.

Obregón's buddy General Benjamín Hill

was probably also assassinated.

It has always been suspected he was poisoned by Plutarco Elias Calles.

Well that stopped in 2000 when Vicente Fox of the

conservative PAN party was elected and defeated

the PRI candidate Francisco Labastida Ochoa,

and became President of Mexico.

PAN in English is the

National Action Party or

Partido Acción Nacional in Spanish.

But the dark side of the new Mexican President Felipe Calderón

is that he appears to be a police state advocate who wants to

bring the Mexican people a police state like Richard Nixon gave to the American people.

At the start of his Presidency he started using the military to crackdown on the drug trade which was never done before.

Currently the American Congress has offered to give the Mexican government billions of dollars of aid to turn its military and police agencies into a well-armed police state like the one we have in America, for a war on drugs in Mexico, like the war on drugs we have in America. And Felipe Calderón wants to take the money.

Most Americans don’t know it but America is the biggest police state in the world.

And that is per our own

numbers issued

by our own government and by the U.N.

When it comes to the number of people in prison per capita

the U.S.A is number one in the world,

and easily out does the old commie nations of

Red China, Russia and the former Soviet Union,

as well as out doing cut rate dictators in

third world countries like Uganda, Cuba, Panama, and South Africa.

The U.S.A has 715 inmates per 100,000 population

while Mexico only has 169 per 100,000 population.

The U.S.A. has 5 times as many people per captia in it's

jails them Mexico has in it's jails.

Here are a few others to compare by

and the number is people in jail per 100,000 population.

The Santa Anna years – 1833 to 1855

If you ask me Santa Anna was one of the greatest crooked Presidents of Mexico.

If you ask me Santa Anna was one of the greatest crooked Presidents of Mexico.

Texas Revolution - Texas War of Independence

October 2, 1835 to April 21, 1836

From what I have read in paper books,

both the Spanish and Mexican governments had a problem with the Indians in Texas.

So they recruited Americans to come to Texas and help them solve that Indian problem.

Of course that is just a politically correct way to say

they recruited the Americans to come live in Texas to help them kill off the Indians.

The borders of the Texas that succeeded from Mexico were considerably different than those of today’s Texas. The lower border only extended to the Nueces River (where Corpus Christi lies today). South of that was the state of Tamaulipas, Mexico. The western border of Texas ended about 200 miles (320 km) west of San Antonio where the state of Chihuahua began, and a 200-mile wide strip of land extended between Tamaulipas and Chihuahua, 100 miles (160 km) southwest across the Rio Grande to connect Texas to Coahuila.

The borders of the Texas that succeeded from Mexico were considerably different than those of today’s Texas. The lower border only extended to the Nueces River (where Corpus Christi lies today). South of that was the state of Tamaulipas, Mexico. The western border of Texas ended about 200 miles (320 km) west of San Antonio where the state of Chihuahua began, and a 200-mile wide strip of land extended between Tamaulipas and Chihuahua, 100 miles (160 km) southwest across the Rio Grande to connect Texas to Coahuila.

Americans overthrow Mexican government in California

June 15, 1846

Under the American dream of “Manifest Destiny”,

it was the dream of American’s that their country would spread from the

Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean.

To make that dream come true many Americans were illegally sneaking

into the Mexican state of Norte California,

hoping they would eventually overthrow the Mexican government,

so the American dream of “Manifest Destiny” would occur.

Mexican-American War

1846-48

The Mexican-American War was an armed military conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848 in the wake of the 1845 U.S. annexation of Texas. Mexico did not recognize the secession of Texas in 1836; it considered Texas a rebel province.

In the United States, the war was a partisan issue with most Whigs opposing it and most southern Democrats, animated by a popular belief in the Manifest Destiny, supporting it. In Mexico, the war was considered a matter of national pride.

On April 21, 1836, the Texans decisively defeated Santa Anna's forces in the Battle of San Jacinto. Santa Anna himself was taken captive by the Texas militia forced to sign the Treaties of Velasco in which he promised to recognize the sovereignty of the Republic of Texas and the Rio Grande as the boundary between Texas and Mexico.

On April 21, 1836, the Texans decisively defeated Santa Anna's forces in the Battle of San Jacinto. Santa Anna himself was taken captive by the Texas militia forced to sign the Treaties of Velasco in which he promised to recognize the sovereignty of the Republic of Texas and the Rio Grande as the boundary between Texas and Mexico.

“We take nothing by conquest.... Thank God.”

1855 The Church and Military lose power

In 1855 Benito Juarez was responsible for the Ley Juárez (Juarez's Law) , and abolished special clerical and military privileges, and declared all citizens equal before the law. Benito Juarez was the only Indian to rule Mexico.

Cinco De Mayo - Battle of Puebla - Batalla de Puebla

May 5, 1862

While Cinco de Mayo or May 5th is a major American holiday

it’s just a minor Mexican holiday.

A common misconception in the United States

is that Cinco de Mayo is Mexico's Independence Day;

Mexico's Independence Day is September 16.

Mexican Revolution

November 20, 1910 to 1919/1929

The Mexican Revolution was brought on by, among other factors,

tremendous disagreement among the Mexican people over

the dictatorship of President Porfirio Diaz ,

who, all told, stayed in office for thirty one years.

During that span, power was concentrated in the hands of a select few;

the people had no power to express their opinions or select their public officials.

Wealth was likewise concentrated in the hands of the few,

and injustice was everywhere, in the cities and the countryside alike.

The Mexican Revolution was brought on by, among other factors,

tremendous disagreement among the Mexican people over

the dictatorship of President Porfirio Diaz ,

who, all told, stayed in office for thirty one years.

During that span, power was concentrated in the hands of a select few;

the people had no power to express their opinions or select their public officials.

Wealth was likewise concentrated in the hands of the few,

and injustice was everywhere, in the cities and the countryside alike.

For most of Mexico's developing history, a small minority of the people were in control of most of the country's power and wealth, while the majority of the population worked in poverty. As the rift between the poor and rich grew under the leadership of General Díaz, the political voice of the lower classes was also declining. Opposition of Díaz did surface, when Francisco I. Madero, educated in Europe and at the University of California, led a series of strikes throughout the country.

For most of Mexico's developing history, a small minority of the people were in control of most of the country's power and wealth, while the majority of the population worked in poverty. As the rift between the poor and rich grew under the leadership of General Díaz, the political voice of the lower classes was also declining. Opposition of Díaz did surface, when Francisco I. Madero, educated in Europe and at the University of California, led a series of strikes throughout the country.

Díaz was unable to control the spread of the insurgence and resigned in May, 1911, with the signing of the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez.

Díaz was unable to control the spread of the insurgence and resigned in May, 1911, with the signing of the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez.

General Álvaro Obregón - 1920 to 1924

General Álvaro Obregón Salido was President of Mexico from 1920 to 1924. Obregon" is a Hispanicize spelling of the Irish surname written as "O'Brien" in English.

General Álvaro Obregón Salido was President of Mexico from 1920 to 1924. Obregon" is a Hispanicize spelling of the Irish surname written as "O'Brien" in English.

Obregón was one of the first Mexicans to comprehend that the

introduction of modern field artillery and especially machine guns,

had shifted the battlefield in favor of a defending forces.

He also grew garbanzo beans or chick peas.

He invented a garbanzo seeder and sold his

product on the profitable export market.

Obregón was one of the first Mexicans to comprehend that the

introduction of modern field artillery and especially machine guns,

had shifted the battlefield in favor of a defending forces.

He also grew garbanzo beans or chick peas.

He invented a garbanzo seeder and sold his

product on the profitable export market.

PRI dictatorship loses power to PAN

For more than 70 years

every 6 years they had a phony election in Mexico

and the people voted in a new President.

Of course the people only had one person to vote for.

And that one person was hand picked by the current President of Mexico.

And that person was always from the

PRI political party or

Partido Revolucionario Institucional in Spanish which is

Institutional Revolutionary Party in English.

If you ask me that sounds more or less like a dictatorship.

President Felipe Calderon a Mexican version of Richard M. Nixon

I liked the new Mexican President Felipe Calderón views on the free market.

I though wow a Libertarian Mexican President how cool.

I liked the new Mexican President Felipe Calderón views on the free market.

I though wow a Libertarian Mexican President how cool.

Sure the Mexican government and police are corrupt.

Most Mexicans know that.

Nevertheless, the level of corruptions in Mexico

and the police state in Mexico don’t even get near the police state in the USA.

If Felipe Calderon and the American government have their way,

our American police state will be exported to the people of Mexico.

And that is sad, I love Mexico as much as I love America.

U.S.A 715 Russia 628 South Africa 400 Mexico 169 England 129 Canada 116